When you go to the children’s garden, it’s amazing what emerges about your own childhood.

When you go to the children’s garden, it’s amazing what emerges about your own childhood.

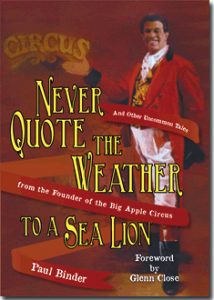

A few years back now, I wrote and published my book Never Quote the Weather to a Sea Lion (and Other Uncommon Tales from the Founder of the Big Apple Circus). I was fortunate enough to have Glenn Close write the foreword for me. I worked with Glenn on the musical Barnum where we worked with the cast and I actually taught her how to juggle. The book is a memoir–it’s a collection of stories from my life both before and during my time with the circus.

Looking back, I’m amazed at how some very important things never made it into the book. I somehow managed to forget whole issues from my childhood. Here’s a very important one that emerged recently.

Me kneeling behind my plaque in St. Armand’s Circle on the day I was inducted into the Circus Ring of Fame

I was down in Sarasota (“Circus City”), where I have a plaque amongst those at St. Armand’s Circle as an inductee into the Circus Ring of Fame. It is, of course as well, the home of Circus Sarasota.

One of the attractions in Sarasota that I’d never visited before (but is a vital part of my education as I always visit attractions that have to do with families and entertainment) is the wonderful Marie Selby Botanical Gardens. One portion of the gardens is designated as the Ann Goldstein Children’s Rainforest Garden, which is absolutely extraordinary. And who better to give me a review and serve as my market-research advisors than my own grandchildren? So Shelley and I took them there.

In the Rainforest Garden, there was a wonderful goldfish pond with those beautiful giant goldfish. You know the kind I mean … the really big ones who can’t wait to be fed so they’re always begging. But what caught my attention was in the center of the pond. There was a beautiful statue of the Buddha. As a tribute to my guided meditation teacher and dear friend, Julie Winter, I asked a woman standing by if she could take a photo of me and the statue and then another photo of the family. She kindly agreed.

After we settled on a couple good photos, I noticed an attractive older couple sitting nearby who I assumed were the woman’s parents. I also noticed that the man had a headset and microphone on, and because we were in a public garden, I asked him if he was a docent (tour guide). And he said to me in a gravely voice, “Oh, no. I have paralyzed vocal chords.”

“Oh, is that a result of arthritis?”

He replied, “No.”

“Really?”

And he said, “I had polio as a kid.”

A waterfall of tears welled up inside of me and I muttered, “So did I,” suddenly recalling a powerful and meaningful story from my childhood.

For two weeks during my childhood, I was bedridden with a high fever and aching legs. The doctor–they made house calls in those days!–would come in daily and measure my legs. I also recall my dad sitting on the end of my bed saying, “You’re a sick little Indian.” My parents were terrified, as all parents were in those days. Remember, please, that this was at the height of the polio epidemic.

The man asked me “What year?”

And I said, “I don’t know. 1949?”

He replied, “Mine was 1951.”

And I said, “Mine too! Because I was 9 years old.”

It turned out that I was lucky. My disease was finally diagnosed as a “non-paralytic form” of polio. Like all diseases, there’s a mystery as to how each of us reacts. Or, as one of my current doctors has said to me, “We’re each our own laboratory.”

Of all things, how could I have forgotten that?

There are intuitive moments in our lives, which most of us often don’t acknowledge. However, part of the Buddhist tradition is to accept these moments as part of the natural human experience. How fitting, then, that I should recall this life experience while posing in front of a statue of the Buddha.